A High Schooler’s Case for Civic Education

By Emory Leonhardt

I’m a high school senior in North Carolina and consider myself lucky. I consider myself lucky because I live in a state where civic education is required.

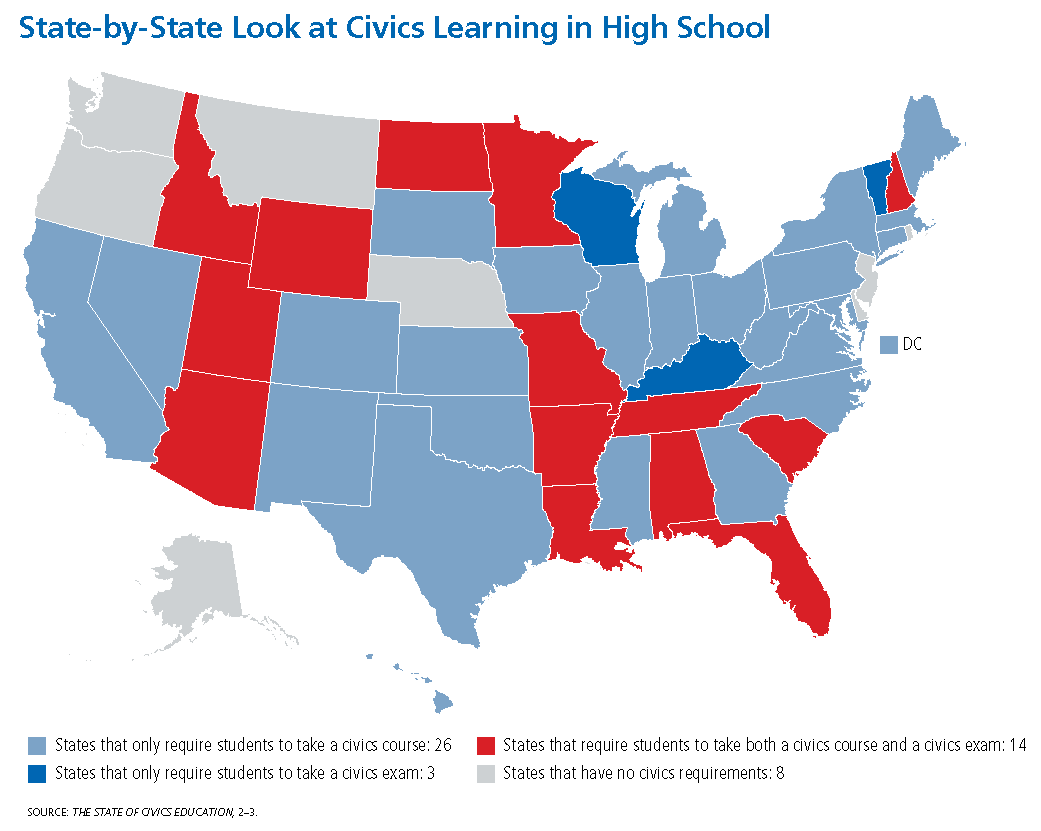

Let me elaborate… North Carolina is one of 31 states in our country that requires half a year of civic education in high school. What about the other states you might ask? 9 states require a full year of civic education and 10 states do not require any form of civic education at all. However, other policy solutions are on the rise. The idea that has garnered the most momentum to improve civics in recent years is a standard that requires high school students to pass the U.S. citizenship exam before graduation. 17 states have taken this path. Yet, critics of a mandatory civics exam argue that the citizenship test only creates another barrier to high school students getting their diploma. In addition to adopting a civic exam or civics class as a requirement for high school graduation, some states have offered community service as a graduation requirement and increased the availability of Advanced Placement (AP) United States government classes.

I have a difficult time understanding how we expect young people to be civically engaged without some kind of civic education. Frankly, I can’t wrap my head around how anyone would be able to understand.

Civic knowledge and public engagement in young people is at an all-time low. A 2016 survey by the Annenberg Public Policy Center found that only 26 percent of Americans can name all 3 branches of government, which was a significant decline from previous years. Educators have an opportunity to ensure that young people become engaged and knowledgeable citizens. In other words, they make sure you can name what the 3 branches of government are!

Civic education is extremely important and it’s worth arguing that it could be critical to getting the younger generation politically engaged. The first step to becoming a politically engaged citizen is becoming educated. If young people do not have a basic understanding of how our government works, how can we be expected to participate in it? It’s simple… we can’t.

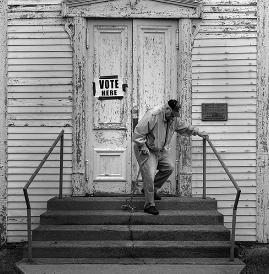

If we are taught about our government in the classroom, even if we are just developing a very basic understanding of it, we are more likely to become engaged when we are old enough to cast a ballot.

This is vital because the reality is you don’t just show up to the polls on Election Day and cast a ballot. You have to register to vote. You have to know how to fill out a ballot. You need to learn about your core issues. You need to learn where you stand on the political spectrum. It is then that you can learn about candidates and their stances on issues that matter to you.

When civics education is taught effectively, it can equip students with the knowledge and skills necessary to become informed and engaged citizens. It has the ability to uplift and empower students. Arguably the most important takeaway from a civics program is that every student feels empowered to contribute to their community—and to their country. Students need to know that even though they may not ever be a politician or work in their government, they still have an essential role to play in democracy.

Expanding civic education sends the message that civics itself is essential to life in a democratic society—that no matter what your role or your job, you have opportunities to participate, and to make the system work better for more people.

My civic education sparked a curiosity and a desire to learn more.

I remember leaving class and wanting to become civically engaged. But what I have come to understand is that being civically engaged does not have a finish line or an end date. There is always going to be more that we can do. The same goes for our civic education. As our government evolves and changes along with our society, there will always be more for us to learn.